The far side of the moon — the part that always faces away from Earth — is mysteriously distinct from the near side. It is pockmarked with more craters and has a thicker crust and less maria, or plains where lava once formed.

Now, scientists say that difference could be more than skin deep.

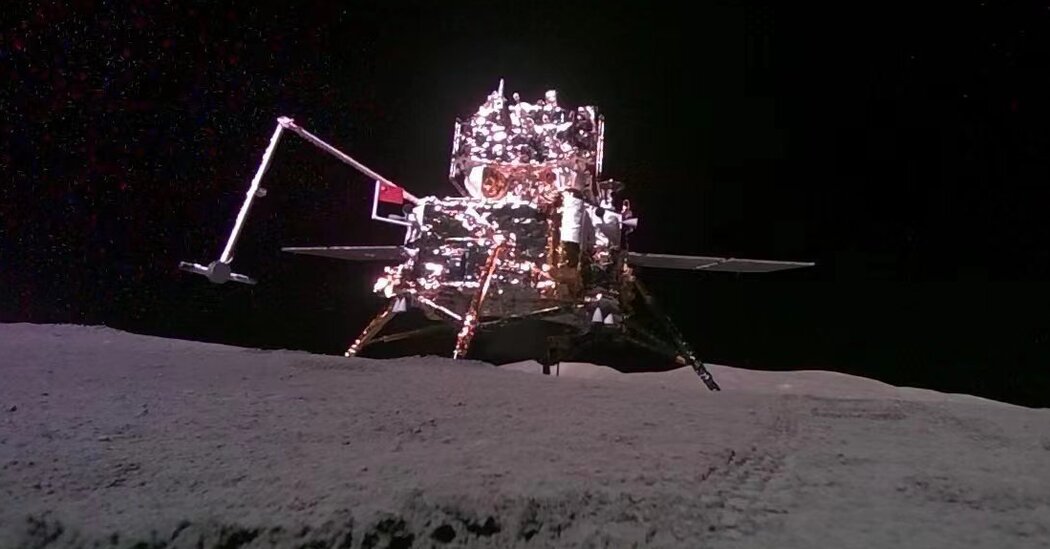

Using a lunar sample obtained last year, Chinese researchers believe that the insides of the moon’s far side are potentially drier than its near side. Their discovery, published in the journal Nature on Wednesday, could offer a clearer picture of how the pearly orb we admire in our night sky formed and evolved over billions of years.

That the water content within the lunar far and near sides differs seems “coincidentally consistent” with the variations in the surface features of the moon’s two hemispheres, said Sen Hu, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing and an author of the new result. “It’s quite intriguing,” he said.

The moon was believed to be “bone dry” until the 1990s, when scientists began to discover hints of water on its surface. Those hints were confirmed when NASA slammed a rocket stage into the lunar south pole in 2009.

One of the goals of this mission and others was to estimate the amount of water deep inside the moon, which helps scientists study its past. The lunar interior is less altered by processes that can weather the surface.

Back on Earth with the Chang’e-6 samples in hand, the researchers sought mare basalts, or hardened grains of lava that erupted from within the lunar mantle. Some of these basalts, as much as 2.8 billion years old, contained olivine, a crystal that formed as ancient magma inside the moon cooled, preserving information about the composition of the mantle early on in lunar history.

The amount of hydrogen trapped in the olivine allowed the scientists to deduce the amount of water present in the mantle back then: between 1 and 1.5 grams of water for every million grams of lunar rock.

Prior measurements from samples collected on the near side of the moon — by the United States, the Soviet Union and more recently China — were as much as 200 times as wet.

The stark difference in the ranges of water content derived from lunar near and far side samples could suggest that the part of the moon invisible to us on Earth is much drier overall, Dr. Hu said.

Shuai Li, a planetary geologist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa who studies water on the lunar surface, described the results as “very interesting.” But he noted that limited information could be extracted from a single sample.

“It’s hard to say whether the far side is definitely drier than the near side,” said Dr. Li, who was not involved in the work.

One scenario proposed by the Chang’e-6 team to explain the interior differences is that the impact that created the South Pole-Aitken basin was powerful enough to fling water and other elements to the moon’s near side, depleting the amount of water on its far side.

Another idea is that the basalts from the Chang’e-6 sample come from a much deeper and drier part of the lunar mantle.

“To me, that is a little bit more realistic,” said Mahesh Anand, a planetary scientist at the Open University in England who was not involved in the study, but helped estimate the water content of the lunar interior from China’s near side sample, collected by the Chang’e-5 mission in 2020.

Dr. Anand also praised the meticulousness of the researchers, who handpicked hundreds of particles from the Chang’e-6 sample, all less than a sixteenth of an inch in size, to estimate the water abundance.

“The ability to do that is quite painstaking, and it requires a lot of sophisticated and careful work,” he said.

More samples from different locations, collected by future lunar missions, will help scientists determine whether the interior on the far side is uniformly parched, or if it varies across the hemisphere.